By Jane Burns

CERES Outreach Education Manager

How well do we respond when the things that work in the background and we take for granted, change or stop working? We’re talking about Recycling.

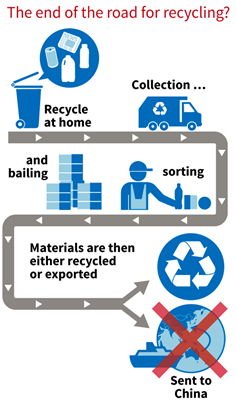

Generally we wheel out our recycling and landfill bins – pretty much on auto pilot – and don’t really think about what happens next. Until perhaps you tuned into the news cycle in January this year and read that China was refusing to take Australia and other countries waste materials under their new ‘National Sword Policy,’ a campaign against yang laji or “foreign garbage” which applies to plastic, textiles, mixed paper and some metals.

Generally we wheel out our recycling and landfill bins – pretty much on auto pilot – and don’t really think about what happens next. Until perhaps you tuned into the news cycle in January this year and read that China was refusing to take Australia and other countries waste materials under their new ‘National Sword Policy,’ a campaign against yang laji or “foreign garbage” which applies to plastic, textiles, mixed paper and some metals.

For Australia this equates to an average of 619,000 tonnes of recycled material to China per year (average between 2012 and 2016). Since the 1980s, China has been the primary destination for waste from Western countries including Australia, the US and UK, and each year more than 30 million tonnes of waste is exported there.

The idiom, one man’s trash is another man’s treasure, may have been true for some years as the materials helped to feed their booming manufacturing industry. But decades later all of China’s major cities are surrounded by piles of imported and domestic waste and many of its people are engaged in processing the refuse in highly toxic environments.

China’s refusal to take foreign garbage is a positive step for China as foreign waste is causing a serious secondary pollution problem. The measure aims to replace imported materials with recycled material collected in its own domestic market to incentivise domestic recycling business, help to raise environmental standards in processing their own waste, increase their recycling practices, and attempt to address domestic concerns over pollution and public health.

At home China already generates about a third of global plastic waste, so clearly it doesn’t need an additional 30 million tonnes of waste to deal with each year!

The oft quoted “There is no such thing as away,” was coined by Annie Leonard, a long time leader in the environmental movement whose project The Story of Stuff went from a movie to a movement. The project inspires us to reflect on having ‘too much stuff’ and take action to redefine our consumer choices. One of several campaigns is the Stop Plastic Pollution which draws our attention to plastic bags but also to the lesser known plastic microfibers that are shed when we wash our polar fleeces and… even our underwear.

The impact of China’s National Sword Policy will be far-reaching because the waste that Australia and other countries exports, is no longer “away.”

It didn’t take long for the commercial process of waste collection to break down in Australia. We heard that some operators in the recycling industry were refusing to accept recycling from several councils, citing that kerbside recycling may not be viable for much longer because there was no one to sell it to. Other councils were planning to stockpile the recycling in the hope the situation changes.

You might be thinking, well this is the stuff of the recycling industry and government, and it’s up to them to fix it. But, the current situation offers business, government and individuals an opportunity to both rethink our relationship to generating waste and view materials as valuable resources that we can put back into the productive economy.

While Victoria recycles most of its waste locally and has a good record of diverting recycling from landfill (64% diversion), China’s new trade measures will affect Victoria’s export of paper and plastic as 33% of all paper and 14% of all plastic was exported to China in 2015-16.

End of the road for business as usual

So whilst Victorians are great recyclers and we need to keep recycling good quality materials that can ideally be recovered and put back into the local economy, we need to first minimise what’s going into recycling bins and into landfill and deal with waste in ‘our own backyard’.

In 2015-16 Victorian’s produced 12.8 millions tonnes of rubbish – enough to fill the MCG every 3 months.

Sustainability Victoria says, a “paradigm shift is required” in how Victoria processes waste, including more effective recycling and the conversion of wasted food into energy. A new report by the agency shows Victorians are projected to generate more than 20 million tonnes of waste each year by 2043.

Victoria’s amended 30-year waste plan awaiting approval, has identified five tip sites or mega landfills on Melbourne’s urban fringe that will handle the city’s waste over that time, in Ravenhall, Werribee, Wollert, Bulla and Lyndhurst. But with some local councils and environment groups challenging the expansion of certain landfills and pushing for alternatives to landfill, the future of the mega landfill as a solution to handle our growing waste is uncertain.

Lobby group Western Region Environment Centre says, recycling more food, which accounts for 35 per cent of the state’s waste, is the best way to cut waste. Victoria has much to improve on food recycling with 92 per cent of food waste going to landfill in 2015-16, and contributing around 40% of what we dispose of.

As Australians what we throw away as food equates to 1 out of 5 bags of groceries we buy!

And food in landfill is a big problem and the result is a greenhouse gas called methane that is 25 times more potent than the pollution that comes out of your car exhaust. There is also a lost opportunity as Sustainability Victoria says of converting wasted food into energy. While at a school and home level, composting our food scraps turn food waste into an end product of free, humus-rich compost!

Time to change our relationship to waste (and stuff)

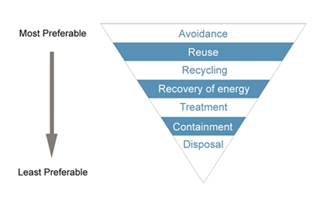

In this waste hierarchy used by the Environment Protection Agency Victoria, the top order is Avoidance followed by Reuse. So whilst Recycling is grabbing all of the headlines, focusing on avoidance and reusing is the only way we’re going to have a different scenario to mega landfills on Melbourne’s urban fringe and exporting our unwanted waste.

In this waste hierarchy used by the Environment Protection Agency Victoria, the top order is Avoidance followed by Reuse. So whilst Recycling is grabbing all of the headlines, focusing on avoidance and reusing is the only way we’re going to have a different scenario to mega landfills on Melbourne’s urban fringe and exporting our unwanted waste.

As Annie Leonard says, We have a problem with Stuff.

So while Governments and industry groups need to impose restrictions and changes to prevent a business as usual approach to generating waste, as individuals we can make different everyday choices and also influence others by our simple, social actions to help reduce waste.

When I read about China’s refusal to take our waste materials, it consolidated in me a change I had committed to but not incorporated into ongoing behaviour. This is a commitment to not buy plastic. I have done Plastic Free July for the last three years and have steadily been reducing my purchase of plastic but the situation with China as well as the global problem of plastic pollution in the ocean was the ah-ha moment when I was aware my half-in approach was part of the problem, not the solution.

Plastic pollution in the ocean is well documented and among the many alarming facts is that humans are polluting the seas at the equivalent to a dump truck of plastic every minute; in three decades, it’s predicted there will be more plastic in the sea than fish. These facts should completely cause us to act to protect the oceans, but the shock value and alarm can cause us to turn away.

Plastic pollution in the ocean is well documented and among the many alarming facts is that humans are polluting the seas at the equivalent to a dump truck of plastic every minute; in three decades, it’s predicted there will be more plastic in the sea than fish. These facts should completely cause us to act to protect the oceans, but the shock value and alarm can cause us to turn away.

Film as a medium combined with talented and well known narrators can reach huge audiences and bring the facts home in a way which helps us to connect to the things we need to care about. Some of these are the nature documentary Blue Planet 11 narrated and presented by Sir David Attenborough and closer to home, War on Waste second episode with Craig Reucassel diving underwater to discover the shocking amount of plastic waste that ends up in our oceans, and Blue the Film written and directed by Karina Holden, a scientist and factual program-maker.

On a smaller scale but showing the impact that individuals and business can have, Australian’s Natalie Woods and Daniel Smith who were determined to live a plastic-free life, founded Clean Coast Collective, a not-for-profit lifestyle brand and action collective to draw attention to the amount of plastic we use unnecessarily every day. They commented,

“We use all of that plastic for half an hour max and then that plastic is going to exist in landfill or elsewhere long after we’re gone, it’ll still be there even after your children’s children are gone.”

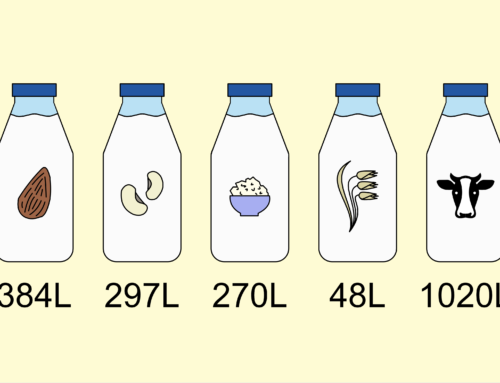

As plastic is in our lives in so many ways, from food packaging to clothing and then disturbingly back into our seafood chain as the marine life eats plastic microbeads and degraded plastic in the ocean – I chose to start my commitment to not buy plastic connected to food. And because the majority of food is packaged in plastic, it was going to have a big impact on my individual contribution to Victoria’s recycling problem.

I already had pretty efficient systems in place for minimising my recycling materials and waste to landfill by composting all of my food scraps, buying unpackaged food in a weekly box from CERES Fair Food, buying dried food and cleaning products in bulk at CERES Organic Grocery, and using a keep bottle and keep cup.

Wormlovers Hungry Bin

Cardia Compostable Bin liner

EcoBin Food Waste Kitchen Caddy Compost Bin

When I started my personal challenge about 5 weeks ago, my kerbside recycling bin was about a third full each week and my landfill bin no more than one bag. Two weeks later the recycling bin was less than a quarter full and last week I didn’t put the bins out as there was so little to recycle.

Finding yoghurt in glass, asking for cheese off the round and only wrapped in paper, making hommus and trying to work out alternatives to buying tempeh in plastic is part of the process of change. Yes it’s inconvenient when you think of it that way, but I feel better knowing I’m making these changes.

We need our elected representatives and industry groups to lead change to alternatives to business as usual but as individuals we can also create change and reducing plastic consumption and composting food scraps are just two examples, but if we collectively did this, the positive impact would be significant.